Being “online” is a permanent aspect of my life, just as it is for many others. I have been aware of this ever since I got my first phone in 2018. The obsession started strong, too—seeing what others were posting, keeping up with trends—so much in one device. Over time, that obsession grew, and now I also scroll through dozens of videos daily to see what people all over the world are doing. With our lives being so interconnected with social media, many forget to take a step back and see the effects. I know that I did.

I don’t often think about how to break this habit, and when I do, it seems too daunting, too hard, and honestly, too boring. I’m used to consuming large amounts of media daily, but how I interpret it has changed drastically. Information travels faster than ever before, and although it has done great wonders for the world, it has also led humans to believe that we can process all this information at once. In Stolen Focus: Why You Can’t Pay Attention – and How to Think Deeply Again, author Johann Hari explains that in a world where everything is too fast, comprehension skills plummet, and focusing becomes harder to do. Humans have made themselves believe that they can “juggle” multiple tasks and thoughts. It’s not possible, and it actually makes performance drop, causes unnecessary errors, and prevents new thoughts and ideas from forming. This attention deficiency is a social epidemic. The way we live has drastically changed, and now we are developing an “attentional pathogenic culture—an environment in which sustained and deep focus is extremely hard for all of us, and you have to swim upstream to achieve it” (Hari 16).

Hari is not the only one who has become aware of this problem. Artist and professor Ben Grosser has started a personal project to reflect on the amount of time he spends scrolling TikTok. His project, Stuck in a Scroll, updates a website with data showing when Grosser is on TikTok, when he last used TikTok, and how much time he has spent scrolling on TikTok since July 1st. Grosser claims this is a last-ditch effort to manage the compulsion he has to scroll every day, as well as to question the narrative of why we scroll so much. Hari explains further in his book that every day, you are “sending out and receiving signals with large numbers of people all throughout the day” (49). When you aren’t, it feels like you don’t matter. B.F. Skinner, a Harvard professor, reinforced this idea with his experiment on animals and focus. He concluded that a human’s sense of focus is just the sum of all the reinforcements experienced in their life. When you are engaging online, you are likely receiving likes, views, comments, shares, retweets, and much more. Gaining these positive rewards makes people want to stay online for longer. When they aren’t, there is always that feeling of needing to check your phone and see what is happening. This systemic problem requires systemic solutions, but there are actions individuals can take to heal their attention.

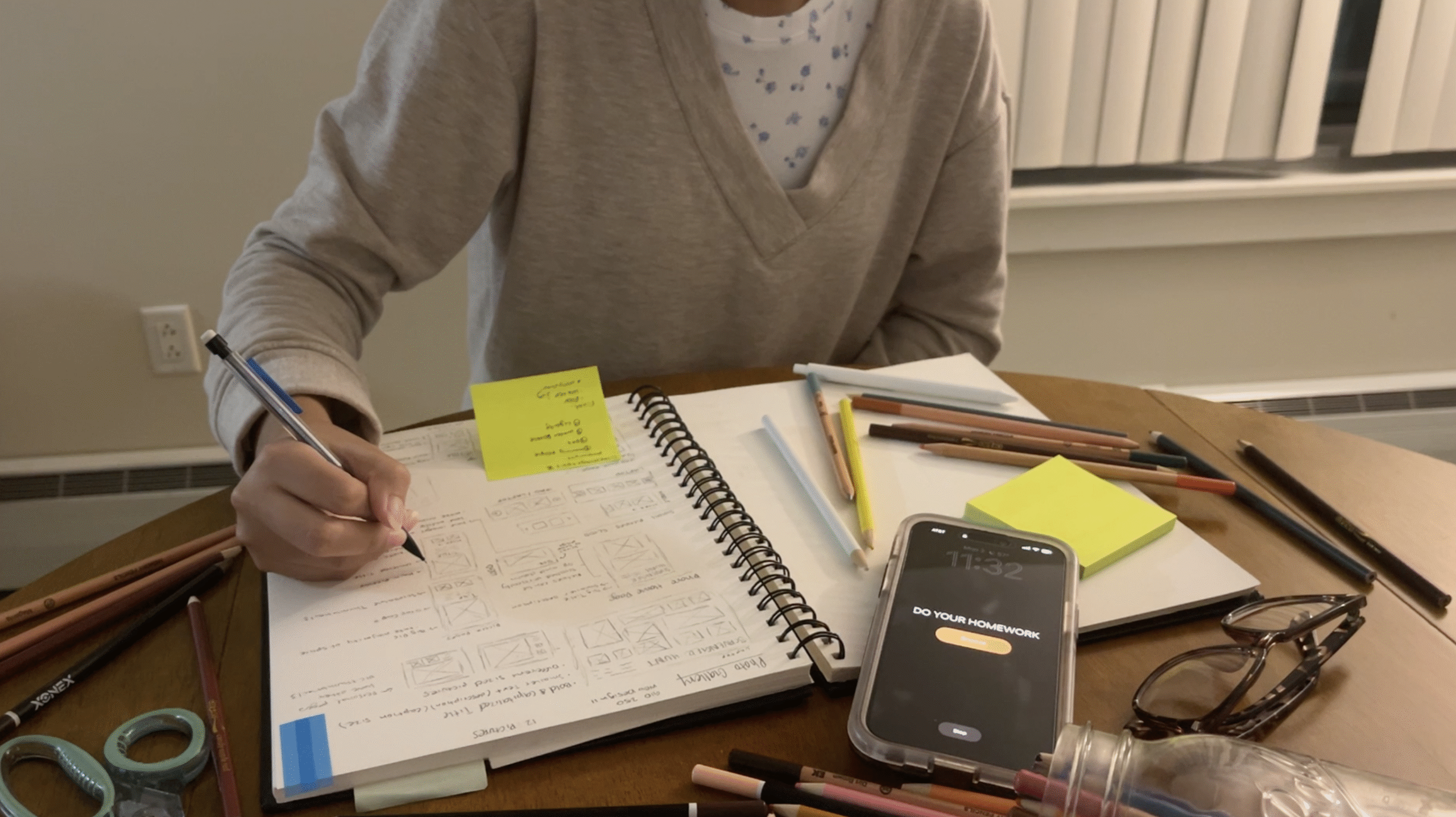

As Hari did in his own journey, he got rid of all distractions. He removed his phone, computer, and even his noisy, busy environment (choosing to stay in a quiet beach town). Hari was learning to live within the limits of his attention resources. Still, he couldn’t seem to focus for long. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi studied the focus of artists and noticed that they were not interested in rewards or money. Instead, they all mentioned being in a “flow state.” This state is the deepest level of focus; you’re absorbed in what you’re doing, losing your sense of self and time. Coincidentally enough, that is what I’m experiencing right now. To write this blog post, I placed my phone in my kitchen and put all my thoughts into writing. It worked; I forgot the time of day and just wrote. This flow state works best when you set a clearly defined goal, do something meaningful to you, and do something at the edge of your abilities. Even so, this form of focusing is experienced when you are actively doing something, like writing. What happens when you do the opposite and slow down to focus?

To test this out, I attempted The NY Times “Test Your Focus: Can You Spend 10 Minutes With One Painting?” assessment. I had one task: to look at a painting for ten minutes. You can stop at any time, but it’s encouraged to analyze the painting. I thought of many things in the first two minutes: the colors, brush strokes, mood. Then I felt uncomfortable, couldn’t think of what else to analyze, and tried my hardest to avoid the “I quit” button or looking at the time of day. I made it to around six minutes, but it taught me much about how I can improve the way I process information. Instead of using my “down time” to scroll on social media, I can look at something new each day and learn more about it. This is less stressful than being bombarded by a million things online and helps me observe things in greater detail without overstressing. These assessments don’t instantly fix our society’s attention deficiency, but they are steps toward realizing there is a problem and moving towards fixing it. Our brain is a muscle; it needs to be exercised every day. The only way to sustain attention is by implementing these practices into our daily life. Just ten minutes can make a difference.